Note: This article is part of an ongoing series titled “The Badass Story of...” These stories feature inspiring tales of actual people throughout history to inspire the hell out of you.

One more note: This issue contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase after clicking the link, we’ll earn some money for coffee, which we promise to drink while thinking fondly of you, you beautiful bastard.

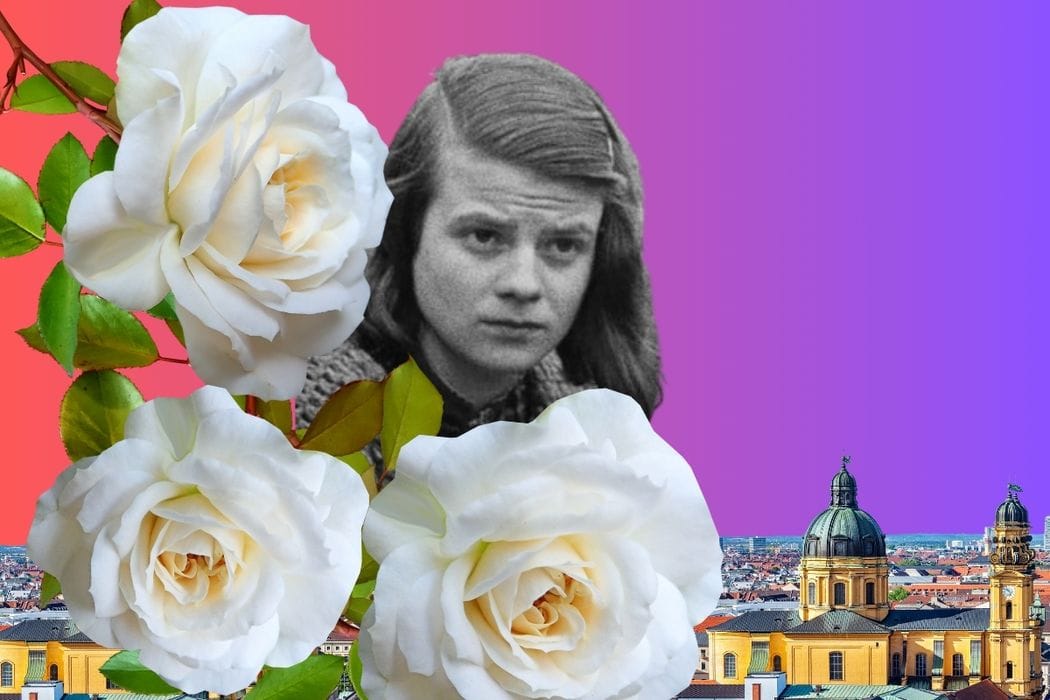

On a bright winter day in Munich in 1943, college student Sophie Scholl was beheaded for her efforts in The White Rose, growing resistance against the Nazi party. She was 21 years old and faced her death with the uncompromising resolve she poured into creating a network of descent among German citizens horrified by the actions of their country’s leadership.

Sophie Scholl had absolute balls of steel, and her fearless actions continue to resonate today. Here is her story.

The Beginning

Sophie Scholl was born in 1921 in Forchtenberg, Germany, a small town overlooking the Kocher Valley in Southwest Germany. Sophie was the fourth of six kids in the Scholl family. Her parents were Magdelana and Robert Scholl.

Sophie’s father, Robert — we will call him Daddy Scholl from this point forward — was a liberal politician and the mayor of their hometown. By all accounts, it sounds like the Scholls led an idyllic life, and Sophie has been described as a bright child who was always eager to learn.

In 1932, Sophie joined the League of German Girls, which has a very benign, girl scout-ish ring to it, but it was, in fact, a wing of the Nazi Party youth movement. But Sophie wasn’t the only one; at the time, most girls her age in Germany joined the League and the true actions Nazi party wasn’t widely known yet. Similarly, her older brother Hans joined the Hitler Youth, which sounds like the worst fucking club that’s ever existed.

In the early 1930s, many viewed the rise of the party as a liberation movement to break the country free of the Treaty of Versailles, pull it out of economic depression, and restore Germany to its former glory.

Daddy Scholl was an outspoken critic of the Nazi Party, as were many of the Scholl’s family friends. Eventually, Sophie and Hans dropped out of their respective little Nazi youth clubs and leaned further into their liberal roots, surrounding themselves with friends who were equally critical of the Third Reich.

The Origins of The White Rose

In 1942, at 20 years old, Scholl enrolled in Munich University, where Hans was studying medicine, to study biology and philosophy.

It was on her first day in Munich that her brother introduced her to his cool friends, Alexander Schmorell and Christopher Probst. Sophie quickly fit right into the group of hot young bohemians. They did what hot, young bohemians do: talked about art and philosophy and made plans to go to the cinema, concerts, and restaurants.

The group’s discussions eventually turned to the Nazi Party and how they could show opposition by connecting with other students and academics who shared their views.

They debated what would be the most effective form of resistance, one that aligned with their non-violent Christian ideals. They decided they would anonymously document their dissenting views in leaflets to secretly distribute through the mail. While this may seem like a benign act at the least, politically aggravating at most, it was a sure death sentence in Nazi Germany. These weren’t annoying college students cosplaying activism; these were young adults with absolute balls few would have the strength to carry.

And so the foundation of what would become the White Rose was laid, with the four students resolved to move forward, accepting that they were putting their lives at great risk.

Shmorell borrowed a Remington typewriter from a friend, and the group began to write.

The introduction to their first leaflet read as follows:

“Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be governed without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today, every honest German is ashamed of his government.

Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes - crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure - reach the light of day?”

Hans spent 32 marks on a duplicating machine (we hereby submit our petition to rename copiers “duplicating machines”) and made 100 copies of the first leaflet. They sent them to addresses they picked from the phone book, most randomly, but some intentionally sent to professors and academics.

They wrote a second pamphlet —

“Now the end is at hand. Now, it is our task to find one another again, to spread information from person to person, to keep a steady purpose, and to allow ourselves no rest until the last man is persuaded of the urgent need of his struggle against this system.

A third pamphlet —

“The defeat of the Nazis must unconditionally be the first order of business; the greater necessity of this latter requirement will be discussed in one of our forthcoming leaflets.”

And a fourth —

“Every word that comes from Hitler’s mouth is a lie. When he says peace, he means war, and when he blasphemously uses the name of the Almighty, he means the power of evil, the fallen angel, Satan. His mouth is the foul-smelling maw of Hell, and his might is at bottom accursed.”

As they spread their message, mailing leaflets to random strangers, tucking pamphlets into phonebooths, leaving them on park benches, and spreading them around cinemas in Munich, they hoped their words were reaching their fellow countrymen who also carried a big "fuck you, Hitler,” in their hearts.

The Soviet Front

That summer, Hans and Schmorell were called to serve as medics on the Soviet front. On July 23, Sophie saw them off, watching her brother and friends depart on a train that would take them through Poland and to the front lines in Russia.

Sophie returned home to Ulm. Her summer was bleak — she was conscripted to work for two months in a local arms factory. Most of the women Sophie worked with were Russian prisoners, and they performed labor Sophie described as “slave-like.” Daddy Scholl served four months in prison as punishment for speaking negatively of man-baby Hitler. Sophie worried about what her brother was enduring on the Soviet front, knowing that when he returned, they would again take up their campaign for resistance to the White Rose.

Sophie worried about what her brother was enduring on the Soviet front, knowing that when he returned, they would again take up their campaign for resistance to the White Rose.

The Soviet front only hardened Hans’ drive to stir opposition to the Third Reich. On the way to Russia, his unit’s train stopped in Warsaw. After nabbing a quick drink, Hans and Schmorel walked the streets, taking in the horrors of the Warsaw Ghetto, where nearly half a million Jews lived in a 1.3 square mile area, cut off from the world.

There is a story about Hans during this time that demonstrates that despite how afraid he may have been, despite the threat of death if the wrong person suspected he was in any way opposed to the regime, he allowed his kindness and humanity to prevail.

While walking to the back of the front lines, he saw a group of Russian women being made to break and carry rocks to make a road. The youngest was a young girl who was clearly weakened with exhaustion. Hans gave her his ration pouch, containing chocolate, nuts, and berries. She refused the ration and threw the pouch on the ground in disgust. Hans then picked a flower and handed it to her when he again handed the rations. He walked away, and as he wrote in his journal, he turned around, and his heart swelled to see her eating the rations, the flower in her hair.

When Hans and Schmorell returned to Munich in November of 1942, the group geared up and resumed their activities as The White Rose.

They spent most nights gathered in either Hans or Sophie’s rented room, discussing how to move forward, and listening to foreign radio broadcasts of spies being caught in the upper echelons of the Nazi party. These reports inspired them and gave them proof that there were others out there.

Find the Authors

As 1942 came to a close and a new year began, the group was re-energized, and Hans and Schmorell each began writing a draft of their fifth leaflet. This time, their message was punchier, more direct, lacking the philosophical and biblical musings of the early leaflets.

“It has become a mathematical certainty that Hitler is leading the German People into the abyss…Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, protection of the individual citizen against the arbitrary actions of the authoritarian states — these are the foundations of the New Europe.”

This time, in step with protests and marches the group felt were reflective of their message reaching others, they produced between 8,000 and 10,000 copies, all on a duplication machine that had to be cranked by hand as copies churned out one by one. Distributing that large number of pamphlets was dangerous— the group again left them in telephone booths, cinemas, and park benches, as well as hiding them in the entrances and stairways of apartment blocks and beer halls. They each traveled alone to different cities in Germany and Austria, carrying hundreds of pamphlets in a suitcase stored in the overhead rack of a different compartment to distance themselves from suspicion.

Distributing that large number of pamphlets was dangerous— the group again left them in telephone booths, cinemas, and park benches, as well as hiding them in the entrances and stairways of apartment blocks and beer halls.

At one point, Daddy Scholl got a hold of one of the leaflets, and although he supported the resistance, he worried for his son and daughter. When he asked Sophie if they had anything to do with it, she lied, “How can you even suspect that?”

Enter the villain of our story (besides Hitler). In Munich, Gestapo police officer Robert Mohr was presented with a copy of one of the pamphlets. His superior told him with alarm that the pamphlets were being found all over the city, calling for all Germans to stage a resistance against the Nazi Party. He was ordered to find the authors of the leaflets and make swift arrests.

Mohr got to work, questioning stationery shops and post offices for any sign of suspicious activity, and through telephoning other Gestapo agencies, he found the leaflets had reached Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Vienna, Ulm, and Augsburg.

Meanwhile, the group worked on their sixth leaflet.

At this time, Sophie wasn’t with her friends but was at home in Ulm, helping her mother and father for ten days. In a letter to a friend, Sophie wrote, “My parents love something wonderful, one of the most beautiful things that has ever been given to me.”

She left home and returned to Munich on February 11. She found Hans and her friends in the middle of their work, having already made 3,000 copies of the sixth leaflet and churning out more. Sophie jumped in to address and stuff envelopes, and Hans went to a store to purchase 1,200 stamps. After he left, the store clerk quietly reported the purchase to the Gestapo.

Meanwhile, Probst had finished writing the seventh leaflet by hand and gave it to Hans, who put it in his jacket pocket.

February 18

Tuesday, February 18, 1943, was an idyllic winter day in Munich. Sophie skipped her first two classes of the day and instead prepared with her brother to distribute the 1,800 remaining sixth leaflets. They placed them in a suitcase– a large one for Hans, a smaller red one for Sophie. They left their apartment at 10:30 a.m. and walked 20 minutes to Ludwig Maximilian University.

The building hall was empty as students were still in lectures. Sophie and Hans worked quickly, laying the leaflets at the feat of the statues, then moving swiftly through the lecture halls, leaving stacks of leaflets outside classroom doors, on window sills, and on the stairs themselves. As they were walking along the balcony looking down into the hall, Sophie had a moment — she grabbed the remaining leaflets in her fists and in one motion, flung them from the top floor of the university into the atrium below when the lecture hall doors opened and hundreds of students stepped into the hall as hundreds of leaflets fluttered to the ground below.

Jacob Schmidt, a maintenance man at the university and bootlicking Nazi asshole, saw the whole thing.

University officials called the Munich Gestapo, where they were patched through to Officer Robert Mohr. Within minutes, the university was filled with officers. Mohr questioned Hans and Sophie in the office of a school official, and he doubted by their middle-class, educated appearance that they could be the ones behind The White Rose. However, it quickly became clear that they were, in fact, the culprits, and they ordered officers to take the pair to Gestapo headquarters. As they walked, Hans quietly slipped the draft of the seventh leaflet out of his jacket pocket, put it in his mouth, and attempted to swallow it. The officers spotted him, wrenched it from his mouth, and gave it to Mohr.

The Interrogation

That afternoon, Hans and Sophie were checked in, searched, fingerprinted, printed, and photographed at the Gestapo prison. Sophie was checked in by a woman named Else Gebel, herself a prisoner who was allowed to do clerical duties. Sophie later shared a cell with Else, who told her, “If you have a leaflet on you, destroy it now.”

The siblings were interrogated separately. Sophie was questioned about her father’s political views and why she opposed the Nazi party.

She told Mohr, “I perceive the intellectual freedom of people to be limited in such a manner as contradicts everything inside of me.” When Mohr asked her about the events earlier in the day, she claimed she was going to go home to Ulm by train but decided to stop by the university first to see a friend. There, she said, she saw leaflets lying around, one pile on the edge of a balcony, which she gave a shove down into the hall below. Mohr sent Sophie back to her cell, where she was given soup, bread, and coffee. He was starting to think the calm young woman was telling the truth.

Back at the Scholl’s apartment, the Gestapo were finishing their search. They found a large amount of envelopes and stamps, a typewriter, and Sophie’s notebook, which contained the mailing list of The White Rose. They, too, found a paper with the same handwriting on it as the one on the leaflet draft Hans had tried to swallow. The officers knew the same person had written both: Christopher Probsts.

Hans and Sophie were integrated throughout the night, and despite being presented with evidence found at their apartment, Sophie stuck to her story. At 4 a.m., after hours of questioning, Hans broke. He told Mohr that he was ready to tell the whole truth. While Hans tried to take all responsibility, once Sophie discovered her brother had confessed, she quickly claimed her part in The White Rose, saying that she and Hans acted alone. However, through further interaction and investigation, the officers would come to know of Schmorell and Probst’s involvement.

Sophie knew that her confession meant she would be executed; even still, like an absolute fucking gangster, she refused to give up the names of her collaborators. When Mohr impressed upon her that her punishment would be the most severe possible, she replied, “I believe I have done the best that I could for my nation. I, therefore, do not regret my conduct. I wish to take upon myself the consequences of these actions.” Legend.

Meanwhile, Probst had been arrested, and he, too, took full responsibility for the White Rose. He pleaded for mercy, saying that he had a wife and three children to look after. But Sophie, Hans, and Probst were to be tried the following day, Monday, February 22, with high treason.

‘And I have to go.’

The next morning, as sunlight poured into their cell, Sophie said to her cellmate Else and said, “Such a beautiful sunny day. And I have to go. But what difference does my death make if our actions alert people?”

Sophie was escorted to the Palace of Justice in a separate police car from her brother and Probst. When the judge arrived, the entire courtroom, except for the members of the White Rose, sprang to their feet and declared, “Heil Hitler!”

Sophie knew that her confession meant she would be executed; even still, like an absolute fucking gangster, she refused to give up the names of her collaborators.

When presented with the evidence, the judge began screaming at the three students, and Sophie, ever the badass, screamed back: “Somebody had to make a start! What we said and wrote is what many people are thinking. They just don’t dare say it out loud.”

Outside the courtroom, Sophie, Hans’ parents, and their younger brother Wernen anxiously awaited the verdict. In the flurry of court resuming from lunch, Daddy Scholl slipped inside and demanded he be allowed to defend his children. The judge ordered him removed, and as he was dragged by guards from the courtroom, he shouted, “There is a higher court before which we all must stand!” Pointing to his children, he cried, “They will go down in history!”

The judge then read his verdict. “In the name of the German People, during a time of war, the accused have called for the downfall of the Reich in leaflets. They aided and abetted enemies of the Reich and demoralized armed forces. The accused are sentenced to death.”

Hans, also ever the badass, shouted at the judge, “Today you hang us, but soon you will be standing where I am now!’

The accused were escorted back to prison, where Hans and Sophie were allowed to meet with their parents in a small visitors’ room. The family said their goodbyes, Sophie only shedding tears after her parents left.

Sophie was executed by guillotine at 5 p.m. that day. In her cell, lying on the bed she had made that morning, was a copy of her indictment for high treason. She had written a single word on the back: “Freedom.”

If you’re not there already, get ready to ugly cry. After their deaths, a copy of the sixth leaflet was smuggled to England. During an airstrike in mid-1943, The Royal Airforce dropped millions of copies of the pamphlet across Germany, retitled The Manifesto of the Students of Munich.

More

What an incredible badass, huh? The story of Sophie Scholl and The White Rose is more than we could fit into our humble newsletter. Learn more about these fearless humans from our recommendations below.

Read

Check out the original White Rose leaflet, both in German and English, on the website for The White Rose Foundation, a nonprofit that upholds the resistance group’s memory and encourages democratic consciousness.

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl

Hans and Sophie’s writings were published in 2017 and offer a glimpse not only into their activities with The White Rose but also their inner thoughts about the war, musings on spirituality and their lives as young-20-somethings, underscoring the remarkable nature of their convictions that ultimately led to their deaths and inspired millions.

Defying Hitler: The Germans Who Resisted Nazi Rule by Gordon Thomas

Defying Hitler details the underground network of German citizens who risked their lives to stand against the Third Reich. It’s full of remarkable stories of resistance, not the least of which is The White Rose. This book was a primary source for today’s newsletter — 10/10, highly recommend.

Watch

The White Rose Young Germans Who Took on the Nazis on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum YouTube

See for yourself

If life ever takes you to Munich, go see the memorial to the brave students, which features replicas of White Rose leaflets are embedded in the pavement outside University of Munich.