This issue contains an affiliate links. If you make a purchase after clicking the link, we'll earn some money for coffee, which we promise to drink while thinking fondly of you, you beautiful bastard.

As Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa gazed at the snowcapped mountains unfurling onto the horizon, they thought of their death.

The young men had scaled a peak in the Andes Mountain range over the course of three days, wearing only layers of socks and plastic shopping bags wrapped around their feet.

Parrado looked at his friend and said, "We may be walking to our deaths, but I would rather walk to meet my death than wait for it to come to me."

Canessa nodded. "You and I are friends, Nando. We have been through so much. Now, let's go die together."

Together, they descended into the valley of spires.

The flight

Two and a half months before, on October 13, 1971, Canessa and Parrado boarded a plane in Montevideo, Uruguay, with 45 other passengers, including Old Christian's Club rugby teammates, family members, and supporters. The team, made up of hot young college students, was to play an exhibition match against an English team once they arrived in Chile. Their flight would take them through the Andes, the longest mountain chain on Earth.

The plane, an FH-227, was in the air for an hour before the co-pilot mistakenly began to bring the plane down, thinking he was near their destination when in fact they STILL WERE IN THE FUCKING ANDES. As the co-pilot attempted to bring the plane back up, it shook with turbulence, triggering an alarm to warn of an impending crash.

And, at this point in our story, we have to ask: CAN YOU FUCKING IMAGINE?

The plane struck a mountain several times, finally ripping the tailbone from the fuselage, killing three people in the tail section. The fuselage slammed into a glacier and slid 2,379 feet at 220 miles per hour before ramming into a snowbank, crushing the cockpit and killing one of the pilots immediately.

Thirty-three passengers were left alive among the mele. Canessa and his fellow medical student Gustavo Zerbino treated those they could help most. Enrique Platero had a piece of metal lodged in his abdomen, which took with it several inches of his intestines when he removed it. Still, like fucking G, he helped his fellow passengers. Parrado sustained a skull fracture and remained unconscious for three days.

The search

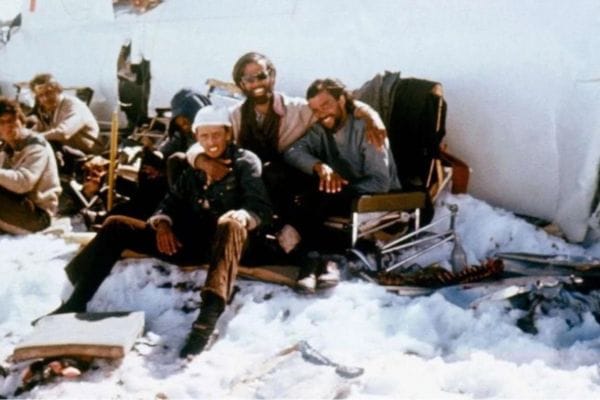

The first night, as temperatures dropped to nearly -22 F, five more died of their injuries. The remaining survivors transformed the fuselage into a shelter, using luggage, seats from the aircraft, and various debris to block the open end and keep in what little warmth there was.

These incredible motherfuckers McGyvered shit in the way that we all think we would but don't actually know if we could. They made a solar-powered water collector with sheet metal, sunglasses with material from the cockpit, bra straps and electrical wires to protect against snow blindness, and snowshoes from seat cushions.

When Parrado awoke, he discovered his mother had been killed in the crash, and his sister was critically injured. Despite his efforts, she died after eight days.

In the first week of their ordeal, the group ate what little food they found among the wreckage, including eight chocolate bars, three small jars of jam, a tin of mussels, almonds, dried plums, and several bottles of wine.

In the meantime, rescue efforts were underway. Three times, survivors saw helicopters and planes flying overhead, searching for the lost passengers. But, the fuselage was white. The snow on the mountains is white. So you know, the air search teams couldn't see shit.

On the eleventh day, they huddled around a transistor radio they found in the wreckage. They were desperate for news that they had been spotted by the rescue crews they had seen flying overhead. Instead, to their horror, they heard the search for them had been called off. Again, we ask, CAN YOU FUCKING IMAGINE?

Eating flesh

Now, we arrive at the part in our story most people know: facing certain death from starvation, the men agreed to eat the dead flesh of their friends, relatives, and teammates who perished before them. Canessa was the first, cutting a small piece of flesh off a body with a shard of broken glass and swallowing it.

Eventually, all of them made the decision to consume the dead. As well, they offered each other permission to eat their flesh in case they died, if it meant that others would live.

The survivors developed a routine of cutting flesh from the bodies — preserved by the frigid temperatures — and drying it in the sun to give it a jerky-like texture. This, survivors reported, made it easier to eat.

On the 17th day, while the group lay sleeping in the makeshift shelter, an avalanche buried the fuselage, killing eight and leaving the others at risk of suffocating. Those who lived spent two days digging a tunnel to the surface.

To the west

In November, the group decided their best chance of making it out of the freezing hellscape was if a few of the strongest surviviors went for help.

Canessa, Parrado, and Antonio Vizintín were elected to walk to Chile, which lay to the west beyond an enormous fucking mountain. They decided to head east in the hopes that the valley would curve around, taking them past the mountain.

The trio was given extra portions of food (flesh) and were excused from chores so they could build their strength for the journey ahead.

The group set off on November 15. After several hours of trudging through the snowy terrain, they found the tail of the plane. Among the wreckage was a box of chocolates, three meat patties, a bottle of rum, cigarettes, extra clothes, comic books, some medicine, and the aircraft's batteries. Facing the risk of freezing to death if they went on, them men spend a the night in the plane's tale. The next morning, they returned to the group.

It was determined that their only hope was for the trio to walk due west and somehow scale the mountain. To keep from perishing in the freezing night cold, the group made a sleeping bag with insulation, electrical wire and waterproof fabric from the plane's airconditioning unit.

On December 12, almost two months to the day that their plane took off, Canessa, Parrado and Vizintín again walked away from their fellow survivors, unsure if they would see them again. These absolutely badass motherfuckers headed straight up the 60-degree slope, with nearly 4,000 feet of elevation ahead of them to the peak of the mountain. On their feet, they wore lays of socks wrapped in plastic shopping bags. Beyond the peak of the mountain, they were certain they would see the rolling green valleys of Chile below.

It took them three days to scale the summit. Below lay not the rolling farmlands of Chile has they hoped, but endless snowcapped mountains.

They were horrified to see endless snowcapped mountains spanning all around them. Their journey for help would take much longer than they had thought. They only had enough food for two of the men to go on, so Vizintín returned to the camp.

"When are you going to come get us?"

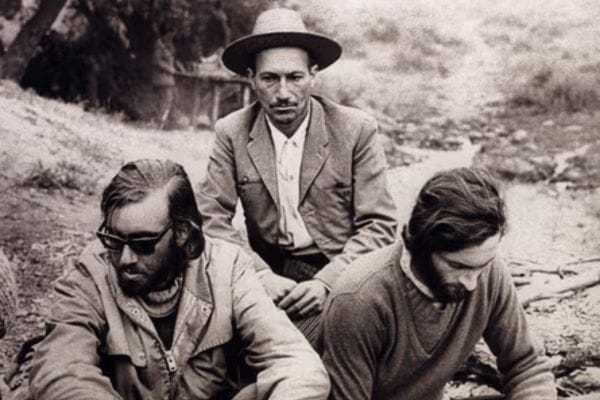

Canessa and Parrado hiked for seven days, covering 38 miles into Chile. The landscape around gradually transformed from a freezing hellscape to green fields. They walked along the Río Azufre, exhausted but hopeful as they saw signs of farmland — and life.

As they built a fire one evening, they saw three men on horseback across the river. Elated, they shouted at the men, but their voices were drowned out by the roaring river.

The next day, one of the men, Sergio Catalán, returned. He scribbled a note on a rock and tossed it to Canessa and Parrado.

Parrado wrote:

"I come from an airplane that crashed in the mountains. I am Uruguayan. We have been walking for ten days. I have a wounded friend up there. In the plane, there were still 14 injured people. We need to get out of here quickly, and we don't know how to. We don't have any food. We are very weak. When are you going to come to get us? Please, we can't even walk. Where are we?"

Catalán threw them bread and rode for help. Parrado and Canessa were rescued that day. Two days later, the remaining fourteen survivors were extracted from their mountain hellscape by helicopter.

As a deluge of attention from the global press fell upon the men, they were faced with one question the world wanted to know: How the fuck did they survive?

The men had agreed to first tell their families of how they resorted to eating the dead. They told the press they ate food from the plane and local vegetation (there was no local vegetation). BUT, on December 26, photos from the rescue sight showing a half-eaten leg were splashed across the front pages of Chilean newspapers, and the public collectively shouted, "What the fuck!?"

During a press conference to address the cannabilism, the young men explained the sacred pact they had with each other, drawing comparisons between their ordeal and the Eucharist.

More

There is SO much more to this incredible story than we could possibly fit in this measly newsletter. The tragedy drew worldwide media attention, resulting in magazine articles, books, mini-series and movies. Here are our recommendations if you want to know more:

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read is one of the most affecting books we've ever read. We even read it on an airplane flying home from Montana to make the experience more vivid.

Along with a blow-by-blow of the accident and subsequent struggle to survive, Read spends time on the personhood of each survivor. The book also tells the harrowing story of the survivors' parents fighting to keep search efforts going and the lengths they went to find their sons. In one particularly gripping scene, one of the fathers is reading off a list of survivors, waiting to see his son's name. 10/10, highly fucking recommend.

Miracle in the Andes is Nando Parrado's first-hand account of the crash and its aftermath. We've never read it, but we plan to.

I Had to Survive: How a Plane Crash in the Andes Inspired My Calling to Save Lives is Roberto Canessa's memoir of his time in the Andes, with rich details of the trek for help.

Society of the Snow by Spanish director J.A. Bayona debuted on Netflix last year. Survivors gave Bayona their full blessings to tell their story. Unlike other theatrical retellings, Society of the Snow includes all 45 passengers and is told in Spanish. The 2-hour and 24-minute film earned praise from critics, viewers, and film festivals, but most of all, survivors consider it to be so accurate that it creates a place to "revisit who they were."

The Andes 1972 Museum is a permanent exhibition in Montevideo, Uruguay, dedicated to the 45 survivors of the infamous crash. On display is a timeline of events, written and oral accounts from survivors, photographs and materials from the plane itself. We have it on good authority that the museum is one hell of an experience.